An important component in the 'selling mechanism' is to how local communities might participate to add

economic value —a community value proposition— from products and services that they can offer directly to the visitor.

This essay is a 'toolbox' of ideas to contribute to this process. The need to employ an expert to guide the project along is a decision for each community.

Now, more than ever, local communities are challenged to better their own economic standing. At the same time, these communities have unprecedented opportunities to make this happen. Research reveals that local people want to be more involved in planning tourism that involves their community but may not possess the proper tools to make this possible. A further problem will be engaging regular people to become involved in creating their future.

Two things are clear: reliance on past performance may not provide clear answers and supporting local enterprises is at the forefront of recovery. Some even go further in emphasizing support for wider community goals and not only monetary benefits. Creativity and finding new ways will bring the best results.

Engagement of local interests brings investment and pride of ownership along with small scale employment and business opportunities. By doing business with other local enterprises, local economies may actually become more stable in the long run instead of relying on the fast return/boom-bust cycle that has been the pattern over the last few decades. One thing is for sure: reliance on outside investors hasn't worked and is not likely to work because there is not the same commitment to the local interests.

Local people also possess attributes such as local culture, food, folklore and knowledge that has great potential to engage visitors and to deliver experiences. This is what the modern visitor is seeking out: local experiences that will be remembered long after the stay.

Equality drives strong, empowered communities to contribute to tourism success whereas, in-equality drives weak and disenfranchised communities to detract from it.

The basis for a successful tourism offering hinges on whether the community has a tourism service oriented attitude. Is there a customer-focussed approach? How willing are residents to accept foreigners in their midst? Is there a mind-set to see past short-term issues such as low revenue or profit projections? Have possible risks and damage to local assets been considered, along with mitigating these impacts? The community needs to possess these things along with a positive outlook in order for community tourism to be successful. The community must be enabled to look at the longer term benefits - and risks - to the community.

In terms of establishing a local tourism centrepiece, or focal point, the first step is engage the community with a goal to create or identify what the community project will be based on. It must be based on something physically present or deliverable, a site, a service or a product. Without this, there really isn't a project. There can be more than one focal point or node. The project becomes a key part of how visitors interact with the community. As observed by Dr. Francesca Zanutto: "The only service that can not be relocated [in] a tourism destination is a PLACE!"

During this phase it is also important to identify stakeholders: individuals, groups or businesses, etc who will be involved in the project or may be impacted by it.

See this 'Example Experience Concept' - 'Bluefields Community led marine reserve experience' (pg 77) in the Community Based Tourism Handbook (CTO).

Is your community connected? If visitors can't get to your location, or are unwilling, what are the chances for success? The next step is to find a way for visitors to travel to your project, and maybe stay for a bit. Echoing the benefits for the community, again ultimately means these benefits will propogate to individuals within the community and to others who come in contact with this place and these people.

This is not a marketing manual, but, clearly how the project will be marketed is important. The project needs visitors to come in, spend some money and support the community. How will the project, and the community, be connected to travel sellers and tour operators?

All of this requires a considerable committment by the community, in money, time and resources. This is also a long term proposition, it will likely take years to get it going and to generate sales and interest, enough to turn a profit and provide financial benefits to the community. At the same time, there is no going back, mistakes and setbacks are going to be a part of the process and it is important to learn from and build on these to improve prospects in the future.

There are other ways to see community tourism. Project undertakings known as "Community Based Tourism Initiatives (CBTIs)" are an example (Simpson, 2007). This is a project, undertaken by entrepreneurs, either within the community, or from elsewhere, to develop a project with a community oriented approach. The main interest is to benefit the community by hiring locals and employ other means to return some financial benefit to the community. The difference from other types of tourism developments is that community involvement and support is accepted and encouraged. This may offer a means by which many of the issues about timing, financing, delays due to disagreements, and so on are not going to stand in the way of development. Even if the community decides to develop their own project, it may be worth while to look at alternatives, if only to better the understanding of what it takes to get a project off the ground.

Sustainable tourism tends to be an abstract concept whereas community tourism has tangible properties. It is better to think about sustainable tourism as coming out of community tourism, rather than the other way 'round. The ability to sustain tourism comes out of the community's ability to come together to create and support a project. This is not meant to infer that community tourism is easy. Its benefits are not always obvious. It likely does not make enough money. It requires a lot of effort and may divide some communities. Many projects end as failures, many are marginal.

So —why do it?

Importantly, community tourism may provide enough incentive for the best and the brightest in the community to stay and help build the community, at least for a time.

In other words, the "success" of a tourism project cannot be viewed solely as the success (or failure) of the project on its own. Some community projects cannot be assessed in financial terms alone. The impacts must be viewed within the context of the whole community and seen as contributing to other aspects of daily life. So, even when it fails there are still benefits that accrue to the wider community. Think of it as a stage in the metamorphosis of the project. Someone else, with a different way to envision the project may be able to turn it into an economically viable project or develop some part of it. The project must never be seen as an outright failure.

Are there examples of projects, or communities, elsewhere that echo some of these issues in your own community? The opportunity to learn from other project experience is valuable, however, it is un-realistic to predict the prospects for success or failure based on the results from another community. The different mix of people, social conditions, history, timing, support and the type of project will all influence relative chances for success. Each project and community must still be assessed independently.

It is beneficial to conceptualize a big project in terms of a set (or series) of smaller projects, as part of an ongoing process. How does each person see their own role in supplying the tourism product?

Create and identify potential collaborative partnerships -- both within the community as well as across all sectors of the tourism industry.

Transport <=> Hotels <=> Attractions <=> Services <=>TOs <=> Guides <=> NGOs

Because of logistical problems, issues of interactions with outsiders, fear of damage to local sites, or fear of "folklorisation", some communities may decide not to develop a project. It is important to garner the support of as large a contingent of residents as possible but some may not agree on a way forward. Will some people benefit more than others? What impact will there be on local youth? In cases where vocal opposition is adamant that a planned project is not beneficial to the larger community, the desired course of action may be to establish as much agreement about ways forward with caution towards the downside factors and respect for dissenting opinions.

Their concerns for community welfare are likely well-founded. To ignore them or downplay them may come back at some future time in a way that could cause serious harm to the project, but more importantly, to the community. These issues must be settled to the best possible compromise of concerns of all citizens.

What are the risks?

The studies showcase a wide variety of "Community Based Tourism Enterprises (CBTEs)" in each country or area. Very often, no two enterprises fit the same model or description, even though they appear, at least on the surface, to be quite similar. This highlights the need to be extremely flexible and adaptable and key to this would be the ability to customize services to fit the 'in-situ' enterprise presence.

Whether individuals are keen to take up tourism services and become actively involved in supplying to tourists is directly related to the successful planning and implementation. Success here will encourage and entice more citizens to participate contributing to long-term success and viability. All citizens will be involved, in some way, whether as a shop attendant, a passerby or service provider and so on. There is potential for interaction between visitors and any of these.

This must be a grassroots kind of participation. Although some initial effort is needed to get the project recognized as viable, this participation must be voluntary and not perceived as being thrust upon or forced. Citizens need to be actively engaged in order to impact the delivery of a product or service as they would want it to be.

This is critical to success. The 'tourism oriented service attitude' is the underlying principal that enables community tourism to flourish. It should be present even if there is no project, in order that residents are engaged in delivering the best experience possible. The objective is to create a positive feedback loop within the community. One that may open possibilities for future development.

Conversely, if local communities do not perceive the benefits from being tourism suppliers than the long-term implications are that tourism will not develop or be willingly accepted by local communities or individuals. This may generate a negative feedback loop, discouraging others from participating. Those residents who do wish to provide the service may end up being frustrated. Their product or service may not have sufficient support within the community to encourage it to fully develop.

This has the potential to block development of tourism on a wider scale. This will impact visitors who may potentially be left with negative impressions from their personal experience. This negative impression is what the destination risks being carried back to be told to friends, and so on -- or worse, to be posted up to social media sites where hundreds or thousands of viewers will read them.

Thirdly, the long-term success of tourism is based on long-term thinking. Many destinations are in the downward phases of the tourism life-cycle. A big part of this is caused specifically by the disenchanted perceptions and attitudes of residents. And what would one expect to be the result after several decades of tourism development that has side-lined, excluded and bypassed these people. This becomes even more problematic when governments bypass their own regulations in order to jump start development.

If tourism authorities - including governments as well as developers - are determined to achieve truly sustainable tourism than this must include the local people. Tourism renewal in many places will be contingent - and conditional - on genuine participation. It is not clear, or even evident, that tourism authorities are willing to take this step without some sort of push. Unfortunately, this may still not be enough to engage people in any meaningful way. So, it may be necessary to determine at least a threshold level of community involvement before tourism projects are allowed to proceed.

Furthermore, many of the best places are in this situation, so finding and developing alternate places is getting more difficult and expensive. However, engaging local people has a high potential to deliver economic, along with social and environmental, improvement. It may make sense to take a new look.

Many local peoples may not possess articulation or literacy skills to express their attitudes in a clear way but this does not mean that they don't have them or that they are unimportant. It does not make sense for leaders to be dismissive and paternalistic - to take a 'father know's best' attitude. This approach is just as likely to re-inforce resentment and perpetuate, possibly deepen any resistance. This is a waste of potential.

The key is to take a future-oriented approach. The past is what happened, it can't be changed. Learn from it and use this to influence the future. You know you can change your future and the future of others that you interact with on a daily basis. It is possible, indeed essential, to harness the people potential - to create positive outcomes and positive experiences for all concerned.

Thinking aloud...

These are not people who can afford to invest a lot of money and then to see their investment not deliver.

By now, probably a lot of communities have considered developing tourism projects but looking at how many have failed, provided they may be aware of them. It would not be surprising if that - by itself - were enough to deter any foray into this realm. However, like most endeavours, nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Not 'if we build it - they will come' but 'if they might come - we might build it': There is little advantage to building something when there are no visitors expected to show up; conversely, if visitors arrive in sufficient numbers, that is when it is time to consider building the project.

So! - Develop the service basics first:

It is possible to think about a set of pre-conditions before embarking in an expensive investment

Are there any outsiders coming into region? (or close by) - If not, why not? or if there are - survey them.

If the above initial studies show positive signs, then:

It may be necessary to 'go back to the drawing board' in instances where a project has been built but has not generated satisfactory results. The project becomes viable when it brings more benefit to people than the collateral harm it might also cause.

There are many questions that need to be answered in order to get at the truth about tourism in the context of communities, some questions might be:

Does your community have the "tourism service oriented attitude"?

Does tourism planning consider all stakeholders? Is anyone left out?

How to deal with serious resistance. Engaging people who object vehemently to understand why they would not support a tourism project.

What about other social and environmental implications?

Does tourism deliver the benefit that destinations - and communities - are yearning for?

Does the destination deliver value and live up to it's billing?

Is the way a culture is shown fair to indigenous people?

Is the tourist paying the real cost to visit the destination?

What are the unexpected/hidden costs, if any? licenses? permits? fees?

Is the tour company/hotel/restaurant/service company paying a fair wage to the local workers?

Are travel suppliers "over-the-top" when promoting their product? Does the destination meet visitor expectations after they arrive?

Are local authorities relaxing rules to allow travel suppliers, such as resorts or cruise ships, to operate?

Are destinations shielding tourists from the true conditions at a destination?

Is the destination a fad, a one-hit wonder?

What happens when the destination no longer attracts? (The Tourism Area Life Cycle or TALC)

What is the role of media?

Community Based Tourism Toolkit: Caribbean Tourism Organisation (CTO)

The CTO has identified Community-Based Tourism (CBT) as a regional development strategy which supports entrepreneurship and community development while also creating unique experiences and product offerings for visitors. The Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) is pleased to share the CBT toolkit developed in collaboration with the Compete Caribbean Partnership Facility (CCPF), under the Innovation for Tourism Expansion and Diversification Project.

Countrystyle Community Tourism Network (CCTN), Jamaica

In association with THE International Institute for Peace through Tourism (IIPT) Caribbean and the National Best Community Competition and Programme (NBCCP), Academy for Community Tourism (ACT) Positive Tourism Network, Hamilton Knight and Associates, University of the West Indies (UWI) Open Campus, Making Connections Work UK, Barbados Community Tourism Network(BCTN), TravelJamii. Founded by Diana McIntyre-Pike.

UNESCO: World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Toolkit

Sustainable planning and management of tourism is one of the most pressing challenges concerning the future of the World Heritage Convention today and is the focus of the UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme.

These 'How To' guides for World Heritage Site managers and other key stakeholders will enable a growing number of World Heritage Site communities to make positive changes to the way they pro-actively manage tourism.

Our Objective: The goal is to stimulate local solutions in communities through capacity-building in best practice. With the immense scale and variation of World Heritage Properties around the globe, coupled with scarce human and financial resources, this is now more important than ever. Site managers and other stakeholders in the tourism sector must have access to these types of innovative sustainability tools in order to develop and formulate their own successful results.

This resource for developing opportunities based on local heritage is as good as it gets.

A Community-Based Tourism Model: Its Conception and Use by Etsuko Okazaki, 2008 ($$)

Community participation in the tourism planning process is advocated as a way of implementing sustainable tourism. There are, however, few studies that detail tangible and practical ways to promote or measure participation. This paper reviews the principal theories used to discuss community participation, including the ‘ladder of citizen participation’, power redistribution, collaboration processes and social capital creation. These theories form the basis for defining a community-based tourism (CBT) model. The paper shows how this model can be used to assess participation levels in a study site, and suggests further actions required. The model is applied in a case study in Palawan, the Philippines, where an indigenous community previously initiated a community-based ecotourism project. The project resulted in a number of problems, including conflicts with non-indigenous stakeholders. The model identifies the current situation of the project and provides suggestions for improvement.

A Guide to Community Tourism Planning in Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Tourism, 2013

This guide will help you prepare a community tourism plan. It is a ‘how to’ document for a

community tourism committee or association, outlining the steps to be taken in doing such a plan.

Best Practices in Integrating Sustainability in Tourism Management and Operations by Carmela Otarra (archive.org, 2019)

"Sustainable tourism development requires the participation of local residents and businesses at the planning stage. By consulting with local stakeholders, you gain their support and reduce conflict as the plan progresses."

Briefing | Make Jamaica an inclusive tourist destination; engage communities, increase youth participation by Dr Andre Haughton, Jamaica Gleaner, Wednesday, December 20, 2017

"There must be a concerted effort to engage communities on a consistent basis to increase the participation of young people in meaningful income-earning activities. "

A Manual for Community Tourism Development, 2005

A manual for sustainable tourism destination management. This manual provides an overview of the complex web of issues that must be addressed in order to manage a destination sustainably. Written by Walter Jamieson and Alix Noble of the Canadian Universities Consortium Urban Environmental Management Project based at AIT.

A Guide to Developing and Supporting a Community Led Sustainable Tourism Program, Planed, Pembrokshire, Wales, 2004 (PDF, original NLA)

A step by step guide and framework which will encourage and enable local people to work together with key partners to develop tourism opportunities which give maximum added value benefits to communities whilst enhancing and interpreting their rich heritage, environment and culture, and utilises local products and services.

Community Based Action in Small Island Developing States*: Best Practices from the Equator Initiative, UNDP, Sept, 2014 (* found at: Federated States of Micronesia: Pacific Environment Portal)

"Communities and islands ... two of the most important building blocks in the future we want – in a future that is inclusive, sustainable and resilient. Their health and well-being will be the litmus test for success.

The past 12 years of the Equator Initiative have surfaced local leaders in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) that are without doubt the global champions we need for sustainable development – for our global community as well as for the future of islands." (Introduction by Gerald Miles, Vice President, Global Development, Rare)

Rare and its partners help empower communities around the world to better manage their fisheries, protect critical watershed habitat, preserve wetlands that harbor endangered species and inspire change so people and nature thrive.

Community-Based Tourism - Option for Forest-Dependent Communities in 1A IUCN Protected Areas? Cameroon Case Study by Shelley Burgin and Eric Fru Zama, 2014

Community-Based Tourism, A Case Study from Buhoma, Uganda, 2005

Community Based Tourism: Perspectives and Future Possibilities by Pimrawee Rocharungsat, PhD Thesis, James Cook U, 2005

Community based tourism initiatives in the Windward islands, Review by Gillian Cooper, 2004 (CANARI Technical Report No. 327)

Community Based Tourism Policy in the Windward Islands by Sylvester Clauzel MSc., BA., CANARI, 2001 (original NLA)

Community Development Through Tourism by Sue Beeton, Landlinks Press, 2006 (Google Books)

Community Participation in the Implementation Process, Barbados Case Study, Nadine Alice Smith, Thesis, 1998

Community Tourism Assessment Handbook edited by Jane L. Brass, Western Rural Development Center, Logan, UT, 1997

A nine-step guide designed to facilitate the process of determining whether Tourism Development is right for your community.

[ Community Tourism Enterprise: Model Case Study Uganda (now requires sign-up) ] | Solimar International | Search for community tourism at Solimar International

Competing with the Best: Good Practices in Community-Based Tourism in the Caribbean, Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Project (CRSTDP), 2013

Ecotourism as a Means of Community Development: The case of the indigenous populations of the Greater Caribbean by Jasmin Garraway, The Association of Caribbean States, 2011

Evolution of the Speyside Eco-Marine Park Rangers from a Community-Based Management Project:

Contributions of the Global Environment Facility – Small Grants Programme in Tobago by Stacey-Marie Syne, UNDP, GEF, 2011 (Original NLA)

A community-based management project in Tobago carried out scientific surveys of the coral reef

ecosystems in the Speyside Marine Area, assessing them as relatively robust and resilient with

consistently high conservation management values.

Guidelines for community-based ecotourism development, Prepared by

Dr Richard Denman, The Tourism Company, WWF International, 2001

These guidelines identify some general principles, and highlight some practical considerations for community-based ecotourism. They seek to provide a reference point for field project staff, and to encourage a consistent approach.

Inter-American Development Bank | Tourism as a tool to fight poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean | Search for: community tourism at IADB (4,640 results)

Inventory and Analysis of Community Based Tourism in Zambia by Louise Dixey, PROFIT Community Tourism Survey, Final CBT Report, November 2005

Linking Communities, Tourism & Conservation: A Tourism Assessment Process, Conservation International, 2006

The goal of Linking Communities, Tourism and Conservation – A Tourism Assessment Process is to help you determine whether a destination is suitable or unsuitable for sustainable tourism. Specifically, this hands-on manual will help you assess a destination’s tourism potential, both negative and positive impacts to biodiversity, as well as impacts on social, cultural and resource needs. The key that opens the door to this clearer view of a destination’s tourism potential is the Tourism Assessment Process (TAP). (Jean Brennan, USAID: RM Portal)

Listen to the Voice of Villages: Research and Analysis, 2010

The objective of the WP3 "Research and Analysis" is to define the most effective and efficient tools

for sustainable tourism development in areas with unexplored potential and tools of governance public

- private, capable of contributing towards the tourism development of the site and having positive

spin-offs on the area and capable of maintaining and increasing attractiveness both for users and for

local residents.

OECS Coalition - Profile and Coalition Terms of Reference St Lucia, OECS, 2014 (@ archive.org, 2015)

This document outlines the agencies responsible for TVET in each of the three countries, the proposed training partners, and the current youth training contexts. St. Lucia and Grenada are both accredited to award the CVQ; for the YSD, one of these countries will be required to provide certification services for the trainees in Antigua and Barbuda.

planeta by Ron Mader

Policy on Community Involvement in Tourism (CIT) in Myanmar

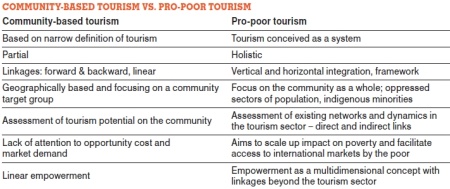

Profession: Tourism Consultant: Mission: To sometimes say no to Community Based Tourism Projects by Nicole Häuslar M.A., 2006

The article explains therefore the components and criteria which must be taken into

account in any case in order to realize a successful CBT-Project. Further, tourism promotion

should no longer be limited to just niche products. Instead, efforts should be shifted to

integrate other sectors more strongly, particularly mainstream and luxury tourism. This is the

only way to optimally utilise the potential which tourism provides for poverty alleviation and

to promote sustainable tourism extensively and, thus, credibly.

Promoting Sustainable Community Based Tourism Through Public-Private Partnerships, Eugenio Peral, 2012

Rural Community Based Tourism in Central America: Case Study, Jodie Keane with Alberto Lemma and Jane Kennan based on an original study by Francisco Perez, Welbin Romero, O. Barrera and A. Palaez, 2009

"Leadership at the community level, clear rules and transparent collective decision making are fundamental elements in the success of this type of local development initiative. The initiatives reviewed in Guatemala and Nicaragua have reached a point of maturity, which has enabled them to connect to the market. This connection continues to be developed, for example in Nicaragua through promotion of the rural tourism network, making individual contact with hotel enterprises and marketing".

Sense of Place: Local communities, responsibility and the visitor experience by Jason Freezer, Conference Theme 3 at RTD7, 2013 (PDF, original NLA**)

Sustainable Community Based Tourism Through Homestay Programme in Sabah, Malaysia by Rosazman Hussin and Velan Kunjuraman, 2014

Sustainable Tourism: Destinations and Communities, Sustainable Tourism Online @ PATA, 2010

Destinations seeking to find a balance between their economic, social and environmental aspirations are engaged in 'destination management'. The internationally recognised VICE model recognises that tourism in a destination is the interaction between: • Visitors • Industry • Community and • Environment

The Community Tourism Guide: Exciting Holidays For Responsible Travellers by Mark Mann (Google Books)

**** Tourism 360 - The Essential Guide for Assessing Your Community’s Tourism Potential by Bill Metcalfe and Mike Stolte, Oct 2011

Whether you’re just starting out in developing your community’s tourism potential or running a sophisticated destination marketing organization (DMO), there’s something here for you.

A critical look at community tourism by Kirsty Blackstock, 2005

Community development has an important role to play in local tourism communities, such as Port Douglas. A CBT that is informed by a community development ethos could provide an important tool for residents who wish to ensure that tourism enhances rather than destroys their communities. With the industry dominating more and more communities in the world, a critical and emancipatory approach to tourism has become essential.

A New Approach to Sustainable Tourism Development: Moving Beyond Environmental Protection by Frederico Neto, UN, March 2003

Abstract:

Tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing industries in the world. It is an increasingly important source of income, employment and wealth in many countries. However, its rapid expansion has also had detrimental environmental (and socio-cultural) impact in many regions. In this DESA discussion paper, I examine the main economic benefits and environmental impact of tourism, and review the development of the international sustainable tourism agenda. While much of international tourism activity takes place within the developed world, this paper will focus on the (economic) development of the industry in developing countries. I conclude that new approaches to sustainable tourism development in these countries should not only seek to minimize local environmental impact, but also give greater priority to community participation and poverty reduction. I argue, in particular, that more emphasis should be given to a 'pro-poor tourism' approach at both national and international levels.

A New Kind of Caribbean Tourism by Alexander Britell, Caribbean Journal, Sept 26 2014

Article about Jem Winston who operates 3 Rivers Eco Lodge in Dominica, which also has a homestay component. Guests are connected to homestay operators, living with them, learning about their culture and interacting with their community.

An evaluation of community-based tourism development: How theory intersects with practice by Dr. Rhonda L. P. Koster, Prairie Perspectives, 2008

What this examination illustrates is that although existing theory does reflect actual practice, there are several aspects of ‘reality’

that the sanitized literature on community-based tourism planning do not adequately reflect.

An Integrative Approach to Tourism: Lessons from the Andes of Peru by Ross E. Mitchell and Paul F.J. Eagles, 2004

Abstract:

This study compares the Andean communities of Taquile Island and Chiquian, Peru, which differ in their level of integration for their respective tourism sector. Integration was primarily defined by percentage of local people employed, type and degree of participation, decision-making power, and ownership in the local tourism sector. Principally social and economic aspects were measured and evaluated, recognising that considerable local support and participation in tourism decision making are linked to issues of ownership and control. It was found that higher levels of integration would lead to enhanced socioeconomic benefits for the community. A framework for community integration was developed that could help guide research, planning, development and evaluation of community-based tourism projects.

Barbados Tourism Master Plan 2014-2023 Final Report I Barbados Latest Tourism Policy Document (Revised May 28 2001) (slideshare)

This paper proposes that Barbados should be positioned as an upmarket, quality destination that focuses on the brand elements of "friendliness", "cleanliness" and the provision of a safe and secure environment and offering the highest possible value for money. (pg iii)

Document places a high level of importance on community participation.

5.4 Involvement of Local Communities

Increasingly, planners and policy makers are recognising the role that local communities must play in the planning, development and operation of tourism if the industry is to be successful. Furthermore, local communities are becoming more aware of their rights and are prepared to express their views in the media and through public demonstrations. Many international funding agencies now include the involvement/treatment of and impact on local communities as one of the conditions precedent to the award of funds for projects. Hence, social impact assessments are now a requirement for many tourism and other development projects.

5.4.1 Factors that Limit the Meaningful Involvement of Communities in the Tourism Industry:

5.4.2 Concerns of Local Communities

The concerns and anxieties of these previously neglected groups need to be understood and adequately addressed in building a successful tourism industry in Barbados.

Some of these concerns focus on the following issues:

9.8 Community Involvement

Government has identified sustainable tourism as the guiding principle for successful tourism development. The tourism industry is essentially a service-oriented sector and one which relies heavily on our human, natural and cultural resources. Communities should, therefore, be encouraged to be involved in all areas of tourism development and the visitor experience to ensure that the service which we provide to our visitors is of the highest quality, and our local resources are conserved and protected. (pg 26)

9.17 Safety and Security

The tourism industry is the major source of income for Barbados and it is imperative that any threat to the sustainability of the industry be firmly addressed and tackled. Crime, harassment, and other forms of anti-social behaviour, along with hazardous and unhealthy facilities are some of the major threats to the development of the industry. Such problems frustrate our efforts at maintaining Barbados’ image as a safe, clean and hospitable destination. The development of community awareness programmes coupled with the strengthening of the capability of our security forces, and the adherence to the highest standards of occupational safety and traffic management are, therefore, essential to our tourism development. (pg 28)

1.3 Foster a climate of empowerment in which each individual is seen as a manager of the tourism product.

1.9 Develop awareness programmes to sensitise Barbadians to the benefits to be derived from engaging in the provision of tourism ancillary products and services. (pg 31)

2.1 Implement initiatives designed to enhance the skills, knowledge and attitudes of Barbadians of all ages, particularly those involved in the tourism sector.

2.4 Continue to work with the Royal Barbados Police Force and other agencies in the reduction of crime and harassment nationally and in the tourism sector. Provide tourism related training for the staff of the Royal Barbados Police Force and other security agencies, and encourage special policing policies for tourist areas.

2.9 Develop a culture of enfranchisement and proprietorship by encouraging employees to invest in the tourist industry. (pg 32)

3.6 Consult/involve the community in all areas of the tourism development process.

3.7 Widen and deepen the involvement of social partners in the planning for and management and operation of the tourism sector. (pg 33)

6.9 Encourage developers to contribute to the social and physical development of local communities. (pg 36)

7.7 Showcase Barbados’ unique cultural heritage, including local products, in our marketing efforts. (pg 37)

10.8 COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

Specific Objective

To encourage and facilitate the involvement of communities in all stages of the tourismdevelopment process.

Strategy/Action - Guidelines

8.1 Develop and monitor action plans for deepening the involvement of ‘communities’ in tourism by inter alia ensuring community consultation in all tourism and tourism-related developments.

8.2 Develop mechanisms, in consultation with relevant agencies, to sensitise communities on the scope and impact of tourism and the opportunities in the sector.

8.3 Create a strategy in collaboration with other government agencies to ensure that communities are consulted throughout the project cycle of tourism related developments which may impact on them.

8.4 Identify appropriate sources of funding for financing community tourism efforts.

8.5 Arrange in collaboration with existing agencies, programmes to develop basic business skills and provide financing in order to facilitate growth of community-based tourism related business.

8.6 Determine the carrying capacity of communities and the effect and impact of tourism on communities through the conduct of social impact assessments.

8.7 Provide fiscal incentives to encourage the development of sustainable community tourism programmes which incorporate indigenous natural resources and cultural heritage. (pg 38)

17.3 Encourage meaningful and effective partnership among the security forces and social partners for the efficient management and control of crime, harassment and other undesirable behaviour. (pg 47)

11.4 Role of Communities

A Social Viability Assessment of Cruise Tourism in Southern Belize, Seatone Consulting, 2011

The findings echo the sentiments of residents in many destinations. They feel that they do not have any say in the development of the tourism industry. They feel that the development has been agreed to without adequate consultation and that the government has not been acting in good faith. They also comment that they do not receive enough benefit after tourism has been developed. This is an example of what can happen when residents are not allowed to participate in tourism development.

"Across the board, citizens and residents of the south repudiated the proposed development concept of a “cruise tourist village” within the village of Placencia. The proposal, in the view of many, typified the exclusive and consolidated nature of the cruise industry—what many consider a problematic element of mass tourism models of development now seen in many parts of the world. Some showed interest in cultivating a market for small ships (e.g. <500 passengers) but emphasized the need to spread economic benefits, ensure local operational control and improve management of the sector in Belize City prior to considering geographic expansion or new port designations in the south. Finally, several meeting attendees expressed frustration at the limited amount of information provided by the private developer, and thus felt ill prepared to offer an informed evaluation or recommendations on the issue to government officials".

Can Tourism Transform?: Community-based Tourism Initiatives in India by Ananya Dasgupta, 2008 (PDF) (Original article taken down**)

In India, tourism is viewed and promoted as a ‘development paradigm’ and a major engine for growth. However,

‘development’ more often than not gets equated with economics, overlooking environmental, social, cultural and

institutional dimensions. Especially in a rural context when the economics of tourism take priority, the impact is far

greater. Rural India is faced with challenges of rising economic inequity, social discrimination and conflicts arising out

of these, as well as differential and poor access to basic civic amenities & services. Therefore when we speak of

tourism contributing to development we need to speak about it holistically – encompassing dimensions of ethics,

equity, and justice, of access, local participation, empowerment, destination competitiveness and ultimately

destination sustainability. A caveat to understanding tourism and development – rural tourism cannot be a one-stop

solution for ensuring goals such as equity and empowerment. However this component is a valuable and critical one if

one were to aim at people centred tourism.

** No copyright infringement intended. If the owner of this article wants it removed, contact info[at]wittreport.com.

Collective Strategies for Rural Tourism: The experience of networks in Spain by Ana Isabel Polo and Dolores Frías, 2010

Abstract: Rural tourism is an increasingly important activity for the European economy. Rural tourism development is complex, considering the wide variety of companies, agents and resources to be jointly managed, the objectives of each participating company, but also to broader objectives relating to the development and conservation of resources in the rural tourist destination. The aim of this paper is to provide a better understanding about the effects of networks as a strategy for improving the development of the rural tourism sector. An in-depth study of networked firms representing a rural tourism consolidated destination found that actions undertaken by networks contributes to the improvement for the rural tourism sector in three areas: improving the performance of enterprises, contributing to the economic and social improvement of rural tourist destinations and helping to create a rural tourist destination image. These findings have implications for both entrepreneurial behaviour and for public agents working in rural tourism.

Communities are key to sustainable tourism development, World Travel & Tourism Council, 2018

Two national tourism heads explain the importance of local communities in the travel and tourism ecosystem.

Community-Based Ecotourism Development: Identifying Partners in the Process by Keith W. Sproule, Wildlife Preservation Trust International, 2001

Abstract:

The focus of this paper is on achieving conservation and development objectives through development of Community-

Based Ecotourism (CBE) enterprises. The premise of the paper is that successful CBE initiatives are supported by the

partnerships of communities with government, non-government and private sectors. To this end, this paper attempts to

evaluate those partners most able to support various initiatives. Finally, the paper provides a few thoughts about CBE

initiatives in the context of a national tourism market and what might be included in a National Community-Based

Ecotourism Development Strategy.

Community-Based Tourism: A success? by Harold Goodwin & Rosa Santilli, ICRT Occasional Paper OC11, 2009

Our approach was to ask practitioners how they would identify a successful CBT initiative, what

criteria they would use; and then to approach those initiatives which had been defined as

successful by funders, conservationists and development workers in order to identify their main

characteristics and, so far as possible, to determine what had been achieved. (pg 4)

There were 116 responses from the experts we asked to identify successful CBT projects and to tell us what criteria that had used. Social capital and empowerment was the most frequently cited criteria, mentioned by nearly 70% of respondents, only 40% of respondents mentioned anything which might be interpreted as referring to the importance of commercial viability, similar to the number mentioning conservation or environmental benefits. Given the prominence of collective benefits in the literature it was surprising that only 12% of respondents mentioned collective benefits as a reason for a CBT initiative being regarded as a success. (pg 5)

Participation is crucial to the formation of CBT initiatives as defined in the literature and whilst it is encouraging that communities participated in the majority of the projects surveyed, there was little to suggest that this was in fact the level of participation that allows for community management, without which the basic premise of CBT is undermined. (pg 6)

The claims made for community empowerment by CBT initiatives cannot be taken at face value, the gains can be important and significant for communities but they need to be demonstrated and subject to critical review. (pg 8)

Mitchell and Muckosy concluded from their review that “the most likely outcome for a CBT initiative is collapse after funding dries up.” They reported that the main causes of collapse were poor market access and poor governance. (pg 11)

[R]esearch by Rainforest Alliance suggests that 40% of CBT projects in developing countries do not involve communities in decision-making, 60% do involve some form of community engagement in decision making. (pg 11)

The large majority of community-based tourism initiatives are based on the development of community-owned and managed lodges or homestays. La Yunga in Bolivia is one such initiative where NGOs encouraged the community to develop a lodge (see Box 1). The lodge has attracted only 60 visitors per year; a bed occupancy of 2.7%. The community subsequently developed a walking trail which in 2005 attracted 1000 people paying $1.80 trail fee, grossing $1800 plus guide fees and other purchases from the community. The example demonstrates that the common focus on accommodation is misplaced – the community benefited far more when it provided an activity, their initiative required a much smaller investment than the investment in the lodge and provided significantly larger benefits. (pg 12)

The jury is still out on whether community based tourism can actually be profitable enough to create sustainable lifestyles, and so support conservation and local economic development. (pg 14)

Conclusions

There are a wide range of reasons given for identifying particular CBT initiatives as successful.

The five main reasons given for initiatives being regarded as successful are Social Capital and

Empowerment, Local Economic Development, Livelihoods, Conservation/Environment and

Commercial Viability.

• Social Capital and Empowerment

This is the most frequently cited reason for a CBT initiative being identified as a success. ± 70%

of respondents cited this as a reason and a quarter of respondents cited this first. This suggests

that for a significant number of respondents the social impacts are of primary importance.

SNV’s review of CBT projects in Botswana suggested that community empowerment can be

considered the most important benefit of CBT. (pg 21)

Sample project in Barbados: de heart uh Barbados

Not considered a CBT, more like a brand. (pg 25)

Again it is important to recognise that some of the non-CBT initiatives make a significant

contribution to the community collectively. For example Manda Wilderness reports that it has

generated earnings which have been used to build “a central clinic, 7 schools, 60 kms of roads

and a market place for the sale of agricultural produce. Set up legal association to protect

communities’ land and civil rights, as well as to create a platform for the communities to

participate in their own development. Boat service and air strip, health and HIV training,

agricultural development. (pg 29)

CBT initiatives are generally small-scale and it is not possible for all members of larger communities to be involved and thus derive benefits; if communities are not able to participate fully, the benefits they derive may be limited; and communities are hierarchical and often elites garner the benefits of CBT development – it is very often the marginalised and poorest members of the community that remain on the periphery which could be down to class, gender, religion, culture or political affiliation. In these circumstances, CBT is not able to deliver on its basic premise of community participation and the equitable share of benefits to all community members. (pg 29-30)

There is a very wide range of different linkages between the projects and the local economy detailed in Table 15 – these linkages are extremely difficult to quantify and to do so was beyond the resources of this research project. It has not been possible to determine whether or not CBT initiatives contribute more than the others, but this is very unlikely as the major determinant of impact is scale. (See Table 15) (pg 30)

Nkwichi Lodge, is run by Manda Wilderness a private company, on a community owned reserve. The lodge demonstrates the significant local linkages which such developments are capable of generating. "The lodge locally sources fruit and vegetables (30%), fish, honey, mushrooms, hand made soaps, woven and carved handicrafts. Use of local choirs and dance groups - $19,000 per annum spent on local procurement. Manda Wilderness has helped set up 3 back packer lodges (rest houses) owned and run by community members. The Agricultural project has worked with over 700 farmers to set up small scale businesses. Assistance has been provided to establish over 10 local shops. Local arts and crafts are purchased from over 15 individuals. All building materials (thatching grass, bricks, timber etc) are purchased from local producers." The survey further reports: "Through knock on effects, all 20,000 people have benefited as there is more cash in the economy and less dependency on barter systems. For example, each village now has a general store / shop - before the arrival of the project, they did not". (pg 31)

Community Based Tourism and Local Culture by Andrea Giampiccolo and Janet Hayward Kalis, 2012

Altogether, CBT can be identified as a strategy for

community development by means of self-reliance, empowerment,

sustainability and the conservation and enhancement

of culture for improved livelihoods within the

community. (pg 175)

This paper suggests that CBT is not a panacea and cannot be seen as the only solution, but it should be included in the framework of strategies to promote rural development. As already noted, if CBT is properly managed it "can provide a range of development benefits to communities, especially in poor and disadvantaged areas". (pg 183)

Note: A parallel result of 'community tourism' may be to re-inforce the idea of 'community' to visitors and what it means to be a cohesive community, see pg 179.

Community-based Tourism in Northern Honduras: Opportunities and Barriers by Jessica Braun, Honours Thesis, 2008 (original NLA)

Abstract: This paper assesses the potential for community-based tourism in Rio Esteban, a small

Garifuna community on the coast of Northern Honduras. The study begins with an

assessment of potential tourism products that could be developed in the community of

Rio Esteban and the neighboring communities. Along with this assessment, barriers to

community-based tourism development were examined at the community level. A

comparison of the barriers at the community level was done with two communities with

differing levels of tourism development: Rio Esteban and Nueva Armenia. An

examination into elements that contribute to successful community-based tourism was

also done at the project level. This was done with a successful project in the community

of Chachaguate and the community of Rio Esteban. From this project, an approach was

developed to how further community-based tourism should progress in the community

of Rio Esteban and the surrounding area. This approach will ensure that communitybased

tourism will become viable and sustainable in the community and will assist in

the economic development of the community.

Each community will face its own distinct set of barriers to CBT development. However, there are persistent barriers that arise in rural communities in developing countries; these include inadequate resources, inadequate infrastructure and poor market access. (pg 3)

Tourism that is going to be community-based or community managed needs to include the community from the onset of its development, beginning with the planning process. CBT initiatives that have employed an inclusive process from the onset of development have shown the greatest success (Cooper 2004). To ensure long-term success of the tourist destination, strong community support and participation is needed in the development process (Tosun 2000). The process should not only be participatory but transparent as well. Transparency will aid in mitigating any conflicts that may arise (Cooper 2004). A community that is engaged in the planning and development process will simultaneously build their capacity for the tourism industry, one of the main barriers initially identified (Mitchell and Reid 2001). (pg 5)

When tourists initially started coming to the island, the women of the island would

compete with each other to see who would feed the tourists (pers. comm. Norales

2008). As a result, the women decided that working together would benefit everyone

and developed the idea of a community-run restaurant. The community was involved

100 per cent in the planning process (pers. comm. Ives 2008). ...

NGO Involvement: The project began with funding from WWF (World Wildlife Fund), GAD, FFEM

(Fundo Frances para el Medio Ambiente), and the Honduran Coral Reef Foundation

(HCRF). The NGOs assisted in the development of the project, provided training along

with providing funding (pers. comm. Ives 2008).

Marketing: The community of Chachaguate has the benefit of being located in a current tourist

destination. The island is situated in the Cayos Cochinos, a group of two islands and 13

small keys that are a marine protected area (Brondo and Woods 2007). The islands are

already marketed by Honduras Tips, the free travel guide available in all major cities in

Honduras. The administrator of the restaurant has made it mandatory for all tours

stopping at the island to eat at the restaurant. This can be done due to the size of island

and a lack of elsewhere to eat in the Cayos Cochinos. (pg 22)

According to Rosy Moya, community leader from Rio Esteban, the project failed

because the development process was not participatory (pers. comm. 2008). The

NGO’s that funded the project did not allow the women’s group leeway for changing

various aspects or for self-coordination. ...

NGO: OFRANEH did not commit fully to the cabana project and did not see it from start to

finish (pers. comm. Ives 2008). The project also suffered from corruption, as all the

funds allocated for the project did not reach the project (pers. comm. Ives 2008).

Marketing: Anthony Ives indicated that one of the major contributing factors to the cabana project

failing was a lack of a business and marketing plan (pers. comm. Ives 2008).

OFRANEH took on the ideology that ‘if you build it, they will come,’ (pers. comm.

Ives 2008). But a lack of marketing resulted in insufficient tourists arriving to the

cabanas and the business becoming unviable. (pg 23-24)

A case study done by Cooper (2004) found that the most effective marketing is done when a marketing brand is developed for a CBT project. A study by Woodland and Acott (2007) also found that local tourism branding is one approach to achieving sustainable tourism. Destination branding is defined as selecting a consistent mix of branding elements to identify and distinguish the destination through positive image building (Cai 2002). Branding elements come in the form of a name, term, logo, sign, design, symbol, slogan, package or a combination of these (Cai 2002). The brand of Rio Esteban will need to incorporate the thoughts and wishes of the community as to assure their tourism product reflects their culture and desires. (pg 30)

Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives - A conceptual oxymoron? Murray C. Simpson, 2007

Abstract:

Tourism is simultaneously portrayed as a destroyer of culture, undermining social norms and economies, degrading social structures,

stripping communities of individuality; and as a saviour of the poor and disadvantaged, providing opportunities and economic benefits,

promoting social exchange and enhancing livelihoods. The aim of this paper is to introduce, define and examine the concept of

Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives (CBTIs) and identify the range of characteristics that contribute to creating the best possible

scenario for a successful, sustainable and responsible CBTI. The paper considers the roles of key stakeholders in CBTIs: government, the

private sector, non-governmental organizations and communities. It seeks to identify the critical components of CBTI development, the

potential problems associated with CBTIs and some of their possible solutions.

Community participation (which can mean a level of control, ownership or influence) in a tourism initiative appears to be closely linked to the derivation of livelihood and other benefits from the initiative to that same community. (pg1)

A community’s sense of ownership, feeling of responsibility and practical involvement in tourism has ... been heralded by researchers and practitioners as central to the sustainability of tourism and of great importance to planners, managers and operators. (pg 1)

The support and cooperation of the local community is frequently integral to those objectives and the path by which to achieve commercial and economic goals may often involve the preservation of essential natural assets, fundamental to the tourism product, and the maintenance of good relations with communities adjacent to or affected by the tourism initiative. (pg 9)

Appropriate tenure and/or ownership rights may assist in protecting the community against the behaviour and attitudes of short-term operators but it is important that sufficient benefits are channelled back to communities and that capacities are built within the community in order that they may deal better with the perennial issues associated with achieving success in the tourism sector. Understanding and appreciating factors such as product positioning, product quality requirements, operations and scheduling, tourism marketing, and the industry’s distribution networks is vital if communities are to sustain their involvement in a tourism initiative. (pg 9)

In essence a combination of conscience, pressure (legislative and lobbyist), necessity and a desire for capturing a maturing and growing market seems to have resulted in more of the private sector’s attention being focused on communities, their needs and the impacts of tourism on their livelihoods. (pg 9)

Tourism initiatives do possess the potential to bring benefits to communities. The same enterprises can also present problems within a community, threaten its stability and harmony, and trigger a range of other factors which menace the economic, environmental and socio-cultural sustainability of the community. (pg 10-11)

To ensure that people’s rights and responsibilities are not infringed upon and to allow those members of the community who wish to do so to continue to pursue their traditional links with land and resources traditional skills should be enhanced not eroded and a tourism initiative needs to complement rather than conflict with the livelihood strategies of individual residents. (pg 12)

Agrigento: 2020 Vision Implementing a Sustainable Tourism Action Plan, Prepared for: Fondazione AGireinsieme By: Martha Honey and Juan Luna-Kelser

Community Engagement Case Studies, Columbia Basin Trust, Davis, 2010 (Excerpt)

Community Engagement – Under the Microscope, Wellcome Trust, 2011 (Health Research)

The Wellcome Trust considers it vital to engage

individuals and communities with science and

health research. Public engagement activities should create a bridge

between the research community and the general public,

community groups, civil society organisations and any

other groups or communities in the outside world where

research gains its relevance.

Community Engagement in Sustainable Development for Local Products by Chris Stone, 2012

While tourism is a desirable industry in many locations, it is also a highly competitive one, and developing a successful destination is a complicated, risky, and frequently prolonged process. The tourist has thousands of destinations between which to choose, so each location needs to develop a distinctive destination product, image, and brand. (pg 246)

Community involvement can be viewed as part of the inexorable ‘democratization’ of public life; as more countries move towards more fully market-based economic systems, citizens demand more involvement in all matters affecting their lives – including issues surrounding tourism development (Gartner, 2005). This in turn links with notions of community empowerment and ‘enabling’ people to create the change they desire at the local level (see for instance Naisbitt, 1984), and also with concepts of social capital - the goodwill, fellowship, sympathy and social intercourse between individuals, families, and groups and associations at destinations which can make positive contributions to economic development initiatives.

Public involvement, ‘democratization’ and community empowerment based upon local social capital constitute rational responses to challenges brought by processes of globalization - including of tourism activity - and their potential impacts at the local level, where citizens want traditional identity-affirming senses of place, neighbourhood, town, locale, and even ethnicity, to survive. ‘Thinking globally and acting locally’ is one interpretation of the term ‘glocalization’ - adaptation to global influences and strategies in accordance with local conditions and expressed preferences (see for instance Swyngedouwa, 2004).

The community approach to tourism development is an attempt to integrate the interests of all community stakeholders, including residents as a critically-important group, in analyses and proposals for development (Murphy & Murphy, 2004). A central part of the rationale for doing so is to address the issue of benefits and costs for both individuals and the wider community. (pg 247)

Developing Innovative Approaches for Community Engagement In the Grand Falls-Windsor - Baie Verte - Harbour Breton Region by Raïsa Mirza, Kelly Vodden and Gail Collins, 2012

Grand Cayman Berthing Facility, Community Engagement Case Studies, October, 2013

Innovation in Tourism: Langley, Abbotsford, Chilliwack, Canada Case Study Project by Megan MacDonald & Ashley Fisher; Cheryl Tourand, Teacher Advisor, 2012 (student paper)

Regional Tourism Cases, Editors: Jim Carson and Dean MacBeth, CRC Australia (Murdoch U), 2005

Community - lots of references

'Community' – A Shared Aspiration - (See: pg 43-45)

While the term ‘community’ invariably conjures up positive images of solidarity, kinship and a

shared sense of place, it is important to acknowledge the difficulties involved in negotiating

community-based projects. The "heterogeneity and complexity of community structures"

(Milne 1998:41) means there will inevitably be a diversity of interests which may lead to

conflict. Community values intersect across a tangled web of associations ranging from class to

ethnicity and communities cannot be assumed to share a commonality by virtue of their

physical proximity. (pg 43)

Rethinking the Public Policy Process: A Public Engagement Framework by Don Lenihan, 2009

Working with 9 provincial and territorial governments through the Public Engagement Project, the Forum developed a Framework Paper that explains what public engagement processes are, why we need them, how they work, and some of the special issues, challenges and opportunities they pose for governments.

[ Tourism & Retail Development: Attracting tourists to local businesses by Bill Ryan, Jim Blom, Jim Hovland and David Scheler, U Wisconsin Extension, 2000 ($$)

This guide to estimating and developing a town tourism potential begins by discussing, among other things, the advantages and disadvantages of attracting tourists, the importance of knowing demographic data of possible visitors, ways of estimating which retail businesses might thrive, and how tourism may change the mix of retail establishments. Ten case studies of thriving Midwest tourist towns are presented. Each study includes descriptions of successful retail businesses as well as observations on what can be learned from that town tourism experience (70 pages; 1999). ]

Wind Energy Development: Best Practices for Community Engagement and Public Consultation, 2011

Social acceptability is key to developing successful projects

Community sustainability in the year-round islands of Maine by Samuel A. McReynolds, 2014

While not written from a tourism perspective, this article does discuss some elements of seasonal issues related to tourism. Tourism is seen as a net benefit bringing revenue into the area but can impact infrastructure, seasonal employment along with wages, property values, product & service availability, and so on.

Abstract: This article examines community sustainability in the year-round islands of Maine, USA, with a critical focus on the impacts of seasonal residents on sustainability. The context of this research is to provide foundational material to determine and measure sustainability in island communities. Data examined includes population, housing, housing affordability, housing occupancy, property valuation, and taxable sales. Food availability is an important secondary consideration. The overall finding is that the island communities as they have historically existed are not likely to be sustainable but may become sustainable in a new form. The overall impact of seasonal residents on sustainability is inconclusive except that there is a clear negative impact in the area of housing. Directions for additional research are discussed.

How Public Participation in Belize Changed the Course of Cruising by Rich Wilson, Seatone Consultants, 2012

So what has come from the aforementioned public consultation process?

Following submission of the cruise report in March 2011, the government of Belize invited Seatone Consultants to share the findings and recommendations at another series of public meetings. During these meetings, government officials stated that they would respect the recommendations and forward the report to the Cabinet of Ministers. The desire by many to not have cruise tourism in the area was openly acknowledged. In addition, officials stressed that the public call for government policies that catalyze job opportunities—that “make rain” as it is said in Belize—had not fallen on deaf ears. The government promised to redouble its efforts to stimulate economic growth in a way that is consistent with sustainability principles and spreads economic benefits to the largest number of Belizeans possible.

If there is a lesson that can be drawn from this story, it is that the power for decision-making in a democratic society can still reside in the public sphere. In looking back, the Belize government should be credited for convening a genuine consultation process that, in the end, gave deference to the greater public interest. On the other side of the social spectrum, Placencia residents have since worked diligently on a local plan for sustained yet sustainable economic growth that creates widespread opportunities in the community. And while the private developers of the proposed cruise port were arguably scared off from this recent act of civic engagement, it is important to note that the issue of cruise industry growth has not gone away. Recent rumors suggest that the industrial port at Independence or offshore gems like the Sapodilla Cayes in the far south are now being considered for visitation by cruise ships. If these rumors show any signs of truth, stakeholders would do well to reference the report—a direct outgrowth of their own hopes, concerns and viewpoints on the issue—to evaluate whether or not cruise tourism on any scale is appropriate for the south.

In the end, the social viability assessment of cruise tourism in southern Belize revealed an earnest desire by multiple stakeholder groups to work closely with government on tourism planning and development issues. In pivoting away from cruise expansion in Placencia, the Belize Tourism Board and Ministry of Tourism have created an opportunity to build stakeholder trust and facilitate cooperation on a host of issues outlined in the Action Plan and National Sustainable Tourism Master Plan, and at a scale and level of civic engagement not previously seen in the region. On the other hand, private sector interests and the wider public may bring a proactive approach to future collaboration based on rational dialogue, openness, mutual respect and shared responsibility. The past development and implementation of whale shark guidelines and environmental performance standards for the marine recreation sector in the area demonstrates strong precedent for precisely this type of effective collaboration. This, in time, has led to economically beneficial outcomes while maintaining the health and resiliency of the region’s natural and cultural assets. It is in this context that the recommendations born of the cruise consultations may provide a pathway to sustainable economic prosperity that grows from the expertise and interests of all public and private sector players throughout southern Belize.

Challenges and Lessons in Financing Community Based Tourism Projects: A business perspective. Case Study by the Saint Lucia Heritage Tourism Programme by Sylvester Clauzel, CANARI, 2008

Key issues around security for loan, record keeping, marketing plan, approval period:

– Collateral security inadequate

– High debt servicing ratio

– Low profit margins

– Lack of statistical data on the CBT/heritage tourism sector

– Lack of familiarity with the CBT/Heritage tourism sector

– The seasonality of the tourism sector

– Poor presentations of proposals and business plans

– Lack of financial information

– Lack of management structures

– Marketing plans and strategies are not in place

– Lack of planning

– Lack of capital

– Inexperience in managing business

Financing is often the make or break stage for a community project, many projects start out with external funding.

Community based tourism is a creative output by communities - projects will not proceed without: creative input, energy input, money input, resource input - cannot be thought of exclusively in terms of money, commercial interest, marketability - the idea being that financing for these projects should be matched by an equal amount of creativity by those supplying the money - institutions, governments, NGOs, individuals. In other words don't expect to dump in a whole bunch of money and then leave the project to either live or die, a further input of creativity and energy must follow the money to support the reason for doling it out in the first place.

What is the value to the financiers to claim support of a successful project?

People who are responsible for securing project need to look at financing agencies to figure out which agency will most likely provide the best chances for success

Barriers to success are already substantial, so concept is to remove, reduce as much as feasible

How is collateral valued?

- No way to measure or place a value on: community equity, sweat equity, intrinsic value, pride of ownership, creative assets

- What is relationship to other community assets?

Assist by providing loan guarantees, tax holidays, financial support ie: matching grants, reduce need to specify purpose of loan, logistical-technical-physical support, progressive performance milestone: credit | incentive | write-off, clear rules and guidelines written in easy to understand language.

Remove need to buy expensive equipment by allowing use of publicly available equipment, for example, computers at librairies

Make use of openly available software

Allow projects to qualify for educational pricing and discounts, at least until the project becomes profitable

If the project generates a product, incent distribution companies to distribute it - bundle it, etc

Key is to think about financiers as partners - they are part of the "community", but on a different level

Most projects are going to fail but don't let this stand as a barier, use the knowledge, experience to build on for future projects, review reasons for failure; SWOT: remove weaknesses, threats and build on strengths, opportunities

What is exchange value of support, if the government wasn't supporting a community project, or, it would need to support the community in other ways, so what money is available to be re-directed into the project?

Think about loan payback terms so that they are proportional to benefit period or term, maybe even think about weighting it so that earlier payment requirements are reduced and payments kick-in when project becomes profitable

In terms of "value chain", where does project fit, do other links need to be supported?

Is there such a thing as default insurance?

Microfinance Gateway | Latin America & the Caribbean

Microfinance in Latin America and the Caribbean (IADB)

MIX Market is a data hub where microfinance institutions (MFIs) and supporting organizations share institutional data to broaden transparency and market insight.

The Five C's of Lending: Cash Flow, Capital, Collateral, Conditions & Character (Community Futures British Columbia)

Community agency and sustainable tourism development: the case of La Fortuna, Costa Rica by David Matarrita-Cascantea, Mark Anthony Brennan and A.E. Luloff, 2010

The study shows how economic, social and environmentally sustainable practices were made possible through community agency, the construction of local relationships that increase the adaptive capacity of people within a common locality. Key factors found to enable community agency are strong intra- and extra-community interactions, open communication, participation, distributive justice and tolerance.

Community Approaches in Tourism Planning at Grass Root Level by Ahmad Puad Mat Som, Badaruddin Mohamed, Jamil Jusoh, Azizan Marzuki and Azizi Bahauddin, 2007 (Malaysia)

A community-based approach to tourism development is a prerequisite to sustainability as the concept of community involvement moves nearer to the centre of sustainability debate. Several advocates of participatory planning in tourism development have argued for an issue-oriented involvement of residents in decisions at an early stage in the decision process, before commitments are made. Thus, community participation in many ways has become an umbrella term for a supposedly new genre of development intervention and an ideology in tourism planning, akin to the participatory planning ideologies in urban and regional planning. By utilizing emic-study method, this paper attempts to appraise the prevailing planning practice and community mechanism at grass root levels in rural areas, particularly in tourism context in this country. In general, it can be contended the level of public participation in Malaysia sits in the first lower quarter of Arnstein’s ladder, and it is more in the form of informing rather than sharing powers to decide on policies and strategies.

Community-based Sustainable Aboriginal Tourism product development: A proposed model by George Ofori, Kapawe'no First Nation Narrows Cultural Resort and Ken Hammer, Malaspina University College, 2005

This paper explores the best approach to solicit community participation in developing a sustainable Aboriginal tourism product. Although brief, there are some very good pointers here.

Community-based Tourism by Maurizio Davolio, President of Earth | European Alliance of Responsible Tourism and Hospitality

Article presents "different definitions of community tourism with strong similarities and some differences which probably originate from diverse sensitivities and experiences gained in specific contexts. However, all things considered, we are talking about nuances, of underscoring rather than actual differences. ...

However, we should not believe that all experiences in community tourism are crowned with success. Unfortunately, in literature and in conferences numerous cases are described regarding failure caused by different reasons – the inadequate previous evaluation of the actual potential and objective conditions; local rivalries and jealousy; errors made by the NGOs, sometimes focused more on the formal achievement of the project rather than on the effective results to be attained; and the absence or weakness of a marketing and communications strategy. The outcome is that the tourists don't arrive, or if they arrive, they leave dissatisfied. The community suffers the frustration of being unsuccessful and the experience is abandoned, or other projects are requested, thus resulting in a practice or mentality of dependence on donors or NGOs, an “easy charity” situation. ...

However, there are also many successful experiences, developed in different countries, from the Caribbean to South America, from both French-speaking and English-speaking African countries, and from the developing Asian countries. ...